6th Airborne Division:

How effective was its contribution to the success of the D-Day landings in Normandy 1944?

Malcolm A. Clough

D-Day Tours of Normandy

A dissertation, posted in seven parts (plus appendices)

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: The Development of British Airborne Forces

Part 3: The Arms and Equipment of British Airborne Forces

Part 4: The Importance of Fire Support provided to 6th Airborne

Part 5: Planning and preparation for D-Day

Part 6: The Actions and Outcomes of 6th Airborne’s Operations

Part 7: Conclusions

.

.

Part 5: Planning and Preparation for D-Day

6th Airborne Division:

How effective was its contribution to the success of the D-Day landings in Normandy 1944?

Malcolm A. Clough

The original COSSAC (Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander) plan for the invasion of Normandy formulated in 1943 proposed to land five allied divisions between the River Orne and the Cotentin peninsula with two more divisions for immediate follow up. These were to be supported by two airborne divisions. However a lack of available shipping restricted the number of assault divisions to three-fewer than had landed in Sicily (Chalfont, 1976:259). On 2nd January 1944 Montgomery was appointed as commander of the ground forces for the forthcoming invasion.

He had seen the original COSSAC plan and set about expanding the assault forces to five divisions with three airborne divisions on the flanks ‘in the east dropped across the Orne to threaten Caen, and in the west dropped in the Cotentin peninsula, to cut communications and to facilitate the capture of Cherbourg’ (Ibid:259)

The shortage of shipping to carry the assault divisions was a major problem. COSSAC, spurred on by Montgomery set about trying to find the extra ships required. The invasion was postponed for a month to allow a rapid construction programme to be completed, British coastal shipping was deprived of 240 of its escorts and the U.S. Pacific fleet transferred 3 battleships, 2 cruisers and 22 destroyers along with 2,483 landing craft. (Ibid: 260). Perhaps most important of all Operation ‘Anvil’ the projected landing in southern France was postponed to allow the transfer of precious equipment, not only landing craft, but gliders and close support vessels as well.

The significant build up of shipping meant there would be enough capacity to carry the five assault divisions to Normandy in one crossing but anymore would be out of the question. If Montgomery was to protect the flanks of his assault force the only way he could achieve it would be to use the allied airborne divisions. By doing so he would effectively land eight divisions in Normandy on D-Day.

It is well known that Field Marshall Erwin Rommel commanding Army Group B in Western France planned to defeat the invasion on the beaches, ‘The most difficult moment for the enemy occurs during the moment of landing itself…he has to be overpowered before he reaches the rim of the coast.’ (Hargreaves, 2006:12) Most of Rommel’s infantry divisions were placed along the coast manning the much vaunted but incomplete ‘Atlantic Wall’ supported by artillery in concrete bunkers. Typically these divisions were second rate, with one in six infantry battalions made up of foreign volunteers mostly from Eastern Europe. (Ibid: 14)

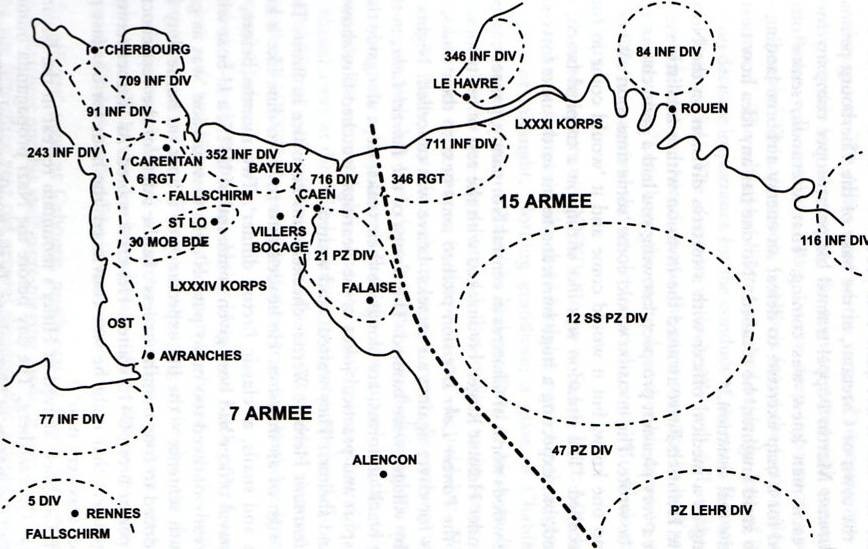

The four crucial Panzer divisions in north- west France were not under Rommel’s direct command, they formed ‘Panzergruppe West’ and were positioned further inland. Panzer Lehr were stationed around Le Mans, whilst the nearest to the coast were 21st Panzer stationed around Caen. Further to the South-east 12th SS Panzer were placed around Lisieux. The task of delaying 21st pz and 12th SS pz’s drive to the beaches on D-day would fall to 6th Airborne Division.

German dispositions in Normandy, 6 June 1944

(Hargreaves, 2006; 35)

On 17th February 1944 General Gale met with Browning to receive 6th Airborne’s orders for the forthcoming invasion. The meeting did not go well for Gale who was bitterly disappointed to learn that because there were insufficient aircraft for the whole division, 6th Airborne were to provide only one parachute brigade and an anti-tank battery to capture the bridges at Benouville and shield the left flank of 3rd Infantry Division. Gale was dismayed; he had hoped that his whole division would be committed to the battle. ‘Gale was convinced that the task was beyond the capability of one brigade, which would face the near certainty of annihilation before reinforcements could reach it’ (Crookenden, 1976:162).

By the summer of 1944, the Royal Air Force still did not possess enough transport aircraft to carry an airborne division into battle in one lift. Unlike the Americans with their DC3/C47 or the German JU52, 38 Group Royal Air Force, who were responsible for transporting the airborne forces, were handicapped by the lack of a suitable British commercial freighter which could be converted to the role of troop transport. Instead 38 Group had to rely on converted bombers for the role and as such had to play second fiddle to the demands of Bomber Command who took priority over manpower and aircraft.

In January 1944 Churchill himself wrote to the Chiefs of Staff ‘I am not at all satisfied with the… plans being made for the carriage of Airborne troops for Overlord…It is clear to me that if strenuous effort is made much more ample resources could be secured” (Crookenden, 1976:67) By the end of the month with the arrival of 150 American C47 transports, No.46 Group Royal Air Force was added to the 180 Stirlings, Halifaxes and Albermarles of 38 Group to create the newly formed RAF Transport Command.

A week after his first meeting with Browning ‘to his joy and relief’ (Thompson, 1989:129) Gale was told that the whole of 38 and 46 Groups would be made available to him. Although there were still not enough aircraft to transport his division in one lift, they would nevertheless go into battle together.

Field Marshall Erwin Rommel directed construction of Hitler’s heavily fortified “Atlantic Wall” defences which were designed to repel any invasion force coming from the sea.

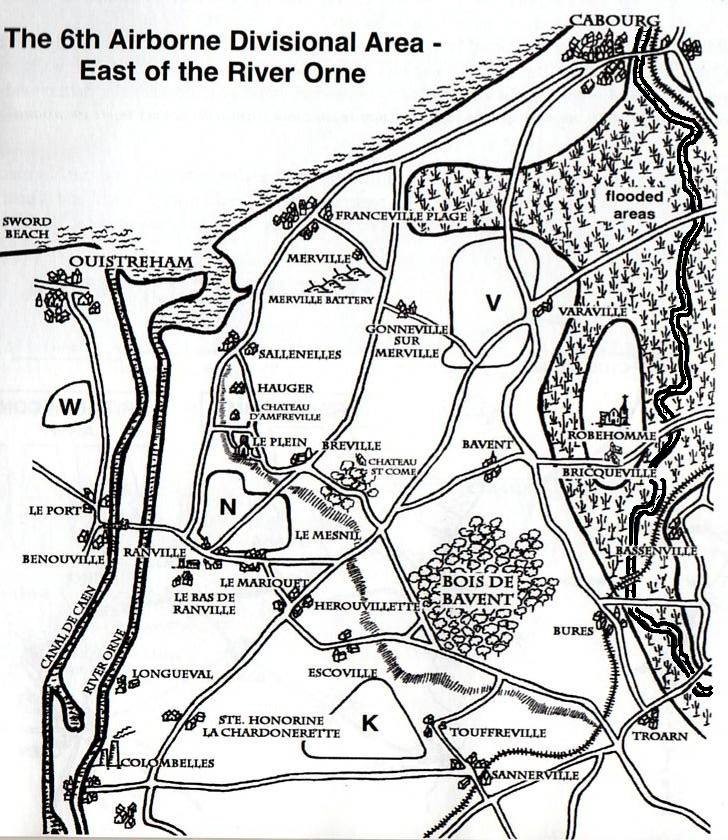

Now that the whole division was to be committed to the battle, 6th Airborne’s role in the invasion was enlarged. The original bridge objectives remained, but with the increased manpower the scope of the operation was broadened to include other tasks. The division was placed under the command of 1st British Corps landing on ‘Sword’ and ‘Juno’ beaches between Ouistreham and Graye-sur-Mer with British 3rd Division on the left and Canadian 1st Division on the right. To the left of ‘Sword’ beach lay the double water obstacles of the Caen Canal and the River Orne, overlooked by a wooded ridge to the east. ‘It was 6th Airborne’s job to protect this eastern flank from enemy attacks and dominate the area between the Caen Canal and the River Dives’ (Clarke, 2004:25)

6th Airborne’s first task would be the capture intact of the two bridges over the Caen Canal and the River Orne at Benouville, The bridges lay three miles inland from ‘Sword’ and a mile to the west of the village of Ranville; described by The Airborne Forces Museum archives as ‘a small village at the heart of what was a most strategic area as it held sway over the region and was relatively easy to secure against attack’ (www.pegasusarchive.org) The bridges across the twin waterways were the only bridges north of Caen between the town and the sea. They were vital not only to the reinforcement and relief of the airborne division on D-Day, but to the future exploitation of the allied bridgehead.

At Merville, four miles to the north-east of Ranville, lay a heavily fortified gun emplacement. The battery overlooked ‘Sword’ beach and was seen as a tremendous threat to the invasion; its four guns thought to be 150mm in calibre, protected by reinforced concrete casemates, could take a terrible toll on the troops coming ashore. General Gale himself described the threat of the Merville Battery ‘Nothing could have been more awful to contemplate than the havoc this battery might wreak on the assault craft’ (Barber, 2002:25)

Three miles to the north and east of Ranville lay a low ridge running southwards for six miles from the mouth of the River Orne to the small town of Troan. Upon the northern half of the ridge lay the villages of Sallenelles, Le Plein, Amfreville and Breville. A mile south of Breville, the dense forest of the Bois de Bavent stretched all the way to Troan, thick with trees and impossible to manoeuvre vehicles in without using its few roads. The ridge was an excellent position to defend and had to be denied to the Germans Occupation of the ridge would allow 6th Airborne to dominate the surrounding area. ‘This ridge although not lofty by any standards, was high enough to overlook the entire British invasion area, and so with both it and the bridges denied to the Germans, they would be unable to challenge the left flank of the invasion area’ (ibid)

Beyond the ridge to the east lay the valley of the River Dives which had been flooded by the Germans to deter airborne landings. The widespread flooding could be used to the Allies advantage if the bridges over the Dives at Troan, Bures, Robehomme and Varaville were destroyed. Consequently German reinforcements, in particular 12th SS pz at Lisieux would be prevented from reaching the battlefield on D-Day.

Major-General R. N. `Windy` Gale, GOC 6th Airborne Division

(Barber, 2002; 24)

Leave A Comment